Af Lærke Levine, projekt- og formidlingspraktikant

20/12/2023

Dansk version længere nede

The effects of the climate emergency do not affect everyone equally; the ways in which climate change affects our everyday lives varies greatly depending on location, socioeconomic status, and gender. In academic and practical contexts, terms such as ‘climate apartheid’ and ‘environmental colonialism’ have been used to conceptualise these inequalities – both in the present but also by acknowledging of the histories that led us here.

These histories include centuries of colonial exploitation and extraction, which have made nations in the Global South more vulnerable to the effects of the climate emergency. This occurred in part by making Global North nations wealthier at the expense of the Global South’s resources, though also through colonial ecological interventions over the past 400 years. In percentages, countries in the Global North have contributed over 90 percent of global CO2 emissions due to overconsumption of fossil fuels – these being the driving force behind the climate emergency – during and after industrialisation.

In current climate-related policy, however, the climate emergency and its consequences are often framed by Global North nations as a shared responsibility – as something we all must work together to mitigate and adapt to. The problem here is twofold: nations in the Global North – which, in many ways, built their current wealth through the exploitation of the Global South – are responsible for this crisis due to overconsumption, but simultaneously expect global action to be taken to mitigate and adapt to the climate emergency. Meanwhile, many nations in the Global South – many of which do not have the same economic resources as those in the Global North due to centuries of colonialism – are faced with some of the most extreme and destructive effects of the climate emergency without the resources needed for climate adaptation, disaster reduction, and rebuilding. To make matters worse, current exploitation of the Global South by Global North companies via offshoring and carbon offsetting continues this cycle, with devastating effects.

What can we do?

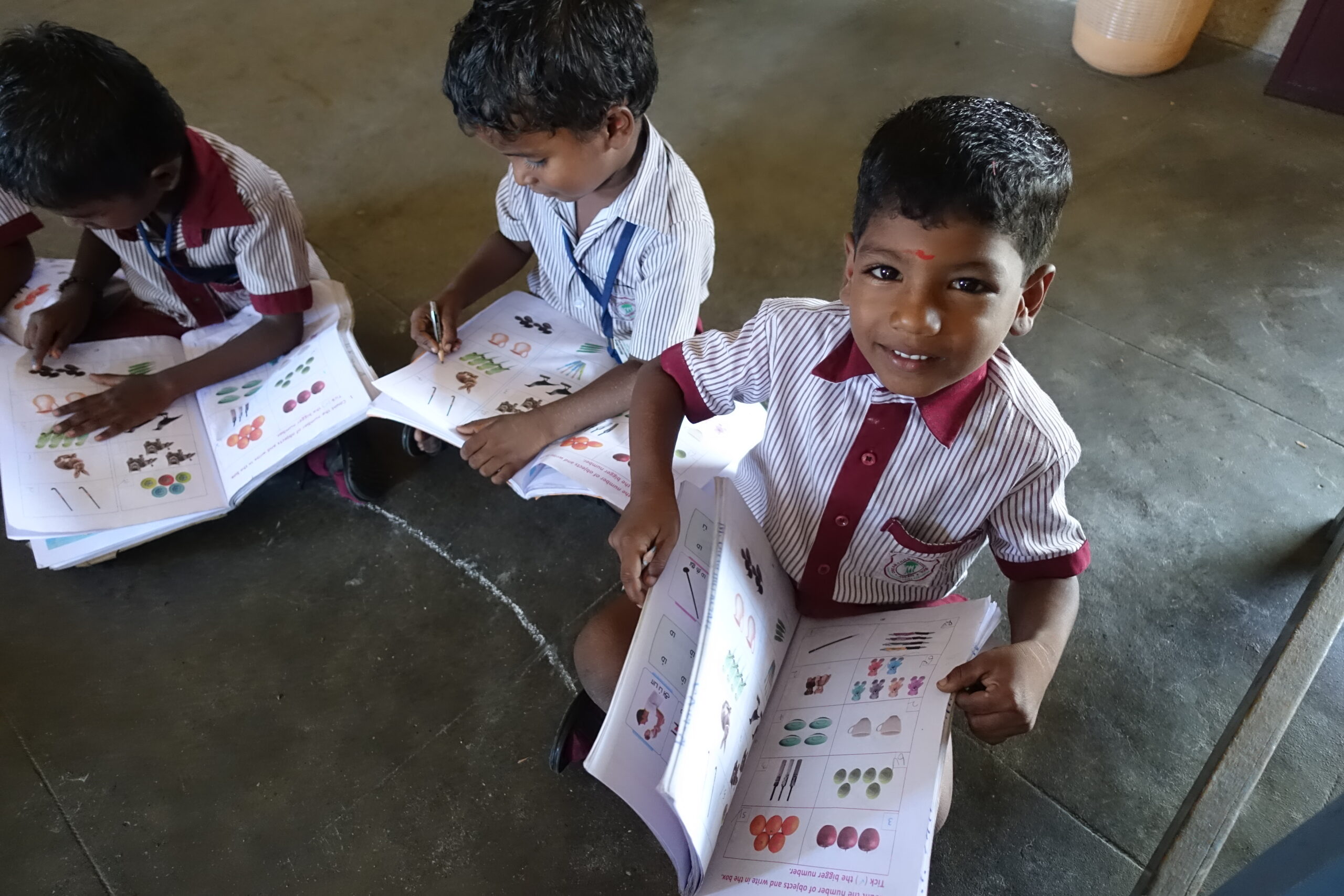

The answer looks different depending on who you are and what you work with. As a small NGO working primarily to promote children’s health, education, and rights in 2 Indian states, Action Child Aid (ACA) does not have the capacity, tools, or relevant experience to address the root problems behind the climate emergency. This does not mean, however, that no action has been taken.

As of March 2023, ACA and local partner Alternative for Rural Movement (ARM) have been working together on the Climate Adaptation for Resilience and Empowerment (CARE) project, in which existing nutrition gardens from the earlier “Family Food Security” project are becoming adapted to the effects of the climate emergency through low-cost, low-resource solutions. Located in the Balasore district of Odisha – a coastal area already prone to flooding and cyclones – the project area has increasingly been affected by more frequent and severe cyclones, making it more difficult to maintain nutrition gardens and thereby reliable access to fresh food. The goal is therefore to strengthen the capacity of these hard-hit rural communities to both mitigate the damage of extreme weather events and build resilience through climate adaptation strategies.

This is by no means a perfect solution, but it is a step in the right direction. As opposed to only telling vulnerable communities that they need to adapt in the face of the climate emergency, the CARE project actually facilitates this adaptation through training, establishment of seedbanks, and support from ARM. Though it will be up to the local communities to maintain their adapted gardens after the end of the project, they are not alone – hopefully, the self-help groups (SHGs) established during the project will continue to support and teach each other after the project finishes, and the methods the communities have been taught will stay with them and help to keep their nutrition gardens more resilient to the effects of the climate emergency.

Further reading

Alston, P. (2019). Climate change and poverty: Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights. United Nations Digital Library. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3810720?ln=en

Davis, M. (2017). Late Victorian Holocausts. Verso Books. (Original work published 2000)

Lewis, A. (2023, June 14). What Is Climate Colonialism? What to Know About Why Climate Change and Colonialism Are Linked. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/what-is-climate-colonialism-explain-climate-change/

Lubinsky, J. (2023). What is Climate Apartheid? | Climate Apartheid, Explained. Climate Culture. https://www.climateculture.earth/5-minute-reads/apartheid-and-the-climate

Rice, J. L., Long, J., & Levenda, A. (2022). Against climate apartheid: Confronting the persistent legacies of expendability for climate justice. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(2), 625–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848621999286

Swami, V. (2003). Environmental History and British Colonialism in India: A Prime Political Agenda. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 113–130. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41949868

Tuana, N. (2019). Climate Apartheid: The Forgetting of Race in the Anthropocene. Critical Philosophy of Race, 7(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.7.1.0001

Dansk version af artiklen

Arbejde med klimatilpasning i ulige kontekster

Konsekvenserne af klimakrisen rammer ikke alle ligeligt; der er stor forskel på, hvordan klimaforandringerne påvirker vores hverdag afhængigt af geografisk placering, socioøkonomisk status og køn. I akademiske og praktiske sammenhænge er udtryk som “klimaapartheid” og “miljøkolonialisme” blevet brugt til konceptualisering af disse uligheder – både i nutiden, men også ved at anerkende de historier, der har ført os hertil.

Århundreders kolonial udnyttelse og udvinding har gjort nationer i det globale syd mere sårbare over for virkningerne af klimakrisen, til dels ved at gøre nationer i det globale nord rigere på bekostning af det globale syds ressourcer, men også gennem koloniale miljøinterventioner i løbet af de sidste 400 år. Procentvis har lande i det globale nord bidraget med over 90 procent af den globale CO2-udledning på grund af overforbrug af fossile brændstoffer – som er drivkraften bag klimakrisen – under og efter industrialiseringen.

I den nuværende klimapolitik fremstilles klimakrisen og konsekvenserne af den ofte af nationer i det globale nord som et fælles ansvar – som noget, vi alle må arbejde sammen om at modvirke og tilpasse os til. Problemet her er tosidet: Nationer i det globale nord – som på mange måder har opbygget deres nuværende væld gennem udnyttelse af det globale syd – er ansvarlige for denne krise på grund af overforbrug, men forventer samtidig, at der gøres en global indsats for at modvirke og tilpasse sig klimakrisen. I mellemtiden står mange nationer i det globale syd – hvoraf mange ikke har de samme økonomiske ressourcer som dem i det globale nord på grund af århundreders kolonial udnyttelse – over for nogle af de mest ekstreme og destruktive virkninger af klimakrisen uden de nødvendige ressourcer til klimatilpasning, katastrofereduktion og genopbygning. For at gøre det endnu værre, fortsætter det globale nords udnyttelse af det globale syd via offshoring og CO2-kompensation denne cyklus med alvorlige virkninger.

Hvad kan vi gøre?

Svaret ser forskelligt ud, afhængigt af hvem du er, og hvad du arbejder med. Som en lille NGO, der primært arbejder for at fremme børns sundhed, uddannelse og rettigheder i to indiske stater, har Aktion Børnehjælp (AB) ikke kapaciteten, værktøjerne eller den relevante erfaring til at løse de grundlæggende problemer bag klimakrisen. Det betyder ikke, at intet er blevet gjort.

Siden marts 2023 har AB og Alternative for Rural Movement (ARM) arbejdet sammen om projektet Climate Adaptation for Resilience and Empowerment (CARE), hvor eksisterende ernæringshaver fra et tidligere projekt bliver tilpasset til virkningerne af klimakrisen gennem low-cost løsninger, der gør brug af de ressourcer, familierne allerede har. Projektområdet, der ligger i Balasore-distriktet i Odisha, er et kystområde der i forvejen er udsat for oversvømmelser og cykloner – og som i stigende grad er blevet ramt af hyppigere og kraftigere cykloner, hvilket gør det sværere at opretholde ernæringshaverne og dermed en stabil adgang til frisk mad. Målet er derfor at styrke disse hårdt ramte landsbysamfunds kapacitet til både at mindske skaderne fra ekstreme vejrbegivenheder og opbygge modstandsdygtighed gennem klimatilpasningsstrategier.

Det er på ingen måde en perfekt løsning, men det er et skridt i den rigtige retning. I modsætning til kun at fortælle sårbare samfund, at de er nødt til at tilpasse sig klimakrisen, faciliterer CARE-projektet faktisk denne tilpasning gennem træning, etablering af frøbanker og støtte fra ARM. Selvom det vil være op til lokalsamfundene at vedligeholde deres tilpassede haver efter projektets afslutning, er de ikke alene – forhåbentlig vil de selvhjælpsgrupper (SHG’er), der blev etableret under projektet, fortsætte med at støtte og undervise hinanden efter projektets afslutning, og de metoder, lokalsamfundene er blevet undervist i, vil blive hos dem og hjælpe med at holde deres ernæringshaver mere modstandsdygtige over for virkningerne af klimakrisen.